New to watching or playing baseball? Knowing the basic rules is critical. We cover all the bases for you here.

Baseball is America’s national pastime, but it might be past time for you to learn how the game is actually played.

Maybe you’ve got a little one getting into tee ball for the first time and you just need to comprehend some of the basics. Perhaps you’re looking for some common ground with a significant other who spends three hours per night for half of the year watching the big leaguers play.

Either way, we’ve got you covered.

How Does Baseball Work? 9 Basic Rules of Baseball

1. Game Duration

You might be wondering why we went with nine basic rules instead of a nice round number like 10. Well, it’s because nine is a significant number in baseball, with one of its fundamental uses being the length of a standard Major League Baseball (MLB) game: nine innings.

To start the game and in the top half of each inning, the visiting team bats (trying to score runs), while the home team is in the field (trying to prevent runs). Once three outs are recorded, they switch sides and the home team bats in the bottom half of the inning.

After each team has nine innings to bat, the team with the most runs wins. (Caveat: If the home team is leading after the top half of the ninth inning, it does not bat in the bottom half of the ninth inning, because there is no need; it has already won the game.) If the score is tied after nine innings, the game goes to extra innings until a winner emerges.

As far as the actual time duration of an MLB game goes, it’s usually a little under three hours.

2. Number of Players and Positions

The other big nine in baseball is the number of players.

There are considerably more than nine players on a roster. For most of the MLB season, there are 26 players per team. However, there are exactly nine batters in the starting lineup and exactly nine players in the field at any given time.

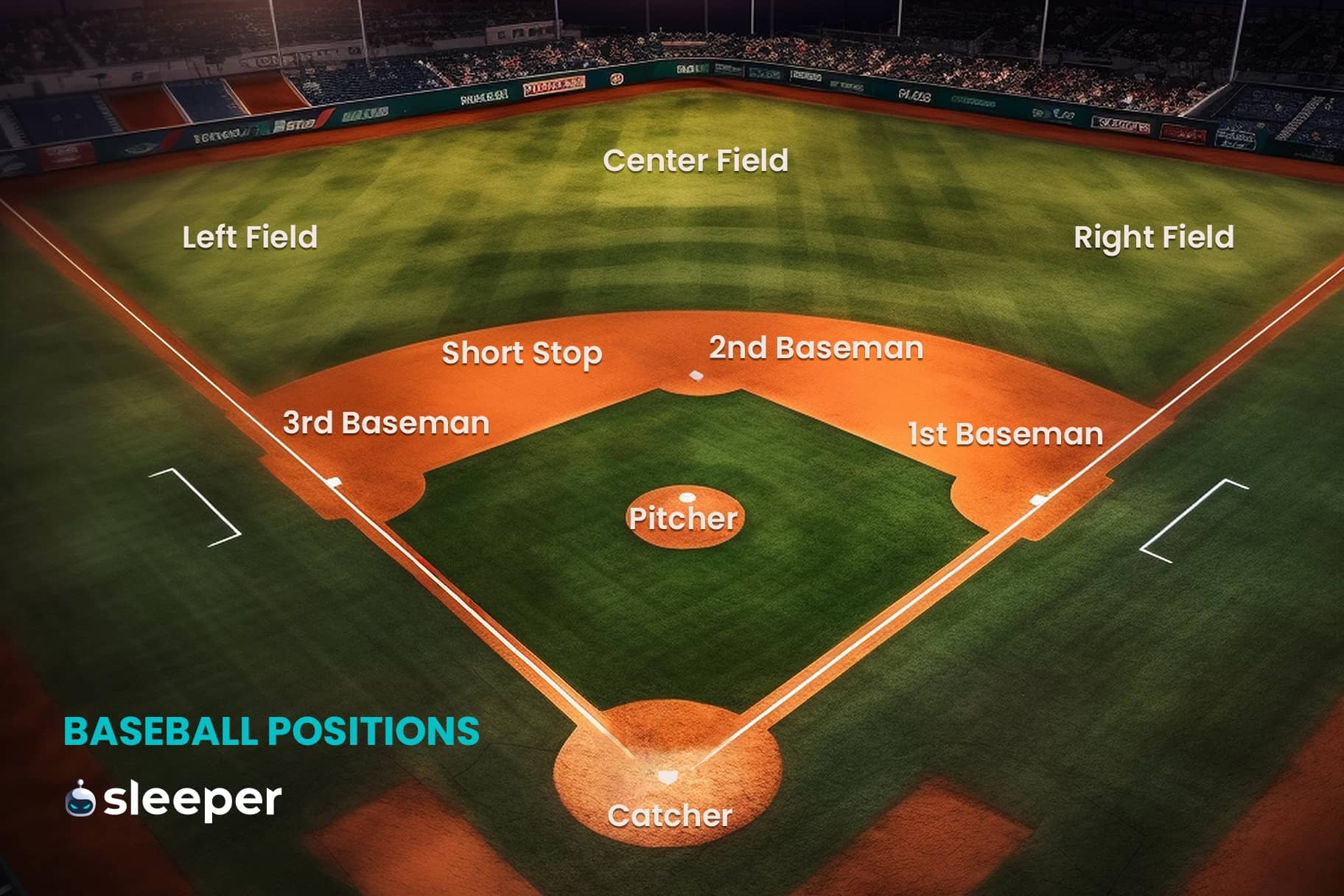

The nine positions in the field are:

- Pitcher

- Catcher

- First Baseman

- Second Baseman

- Third Baseman

- Shortstop

- Left Field

- Center Field

- Right Field

Those are also the batters, with the exception of there being a designated hitter in place of the pitcher.

3. Field Dimensions

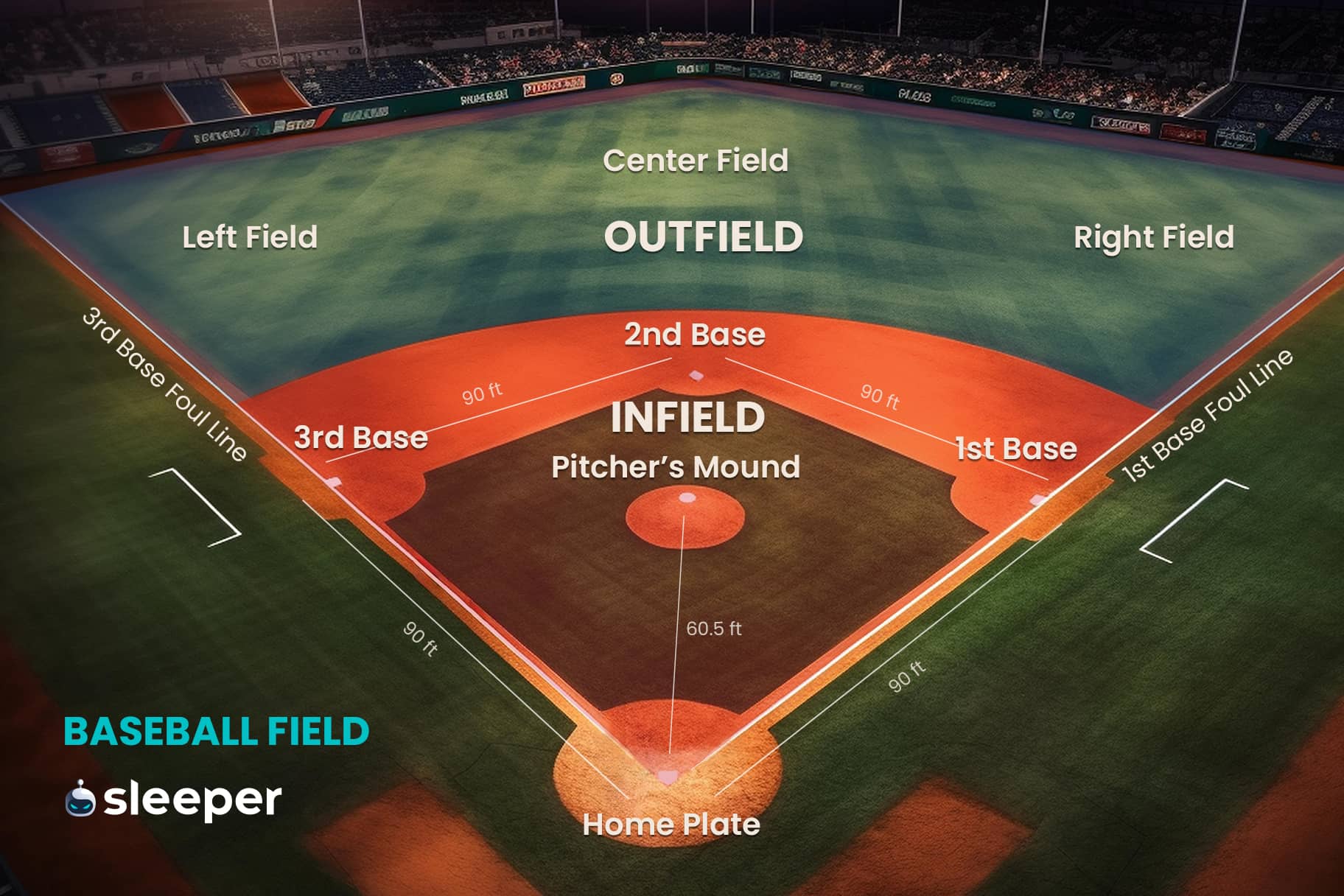

In the majors, 90 feet separates each base. The other standard measurements are that the pitcher’s mound is 10 inches higher than home plate and there are 60 feet, six inches of distance between the two.

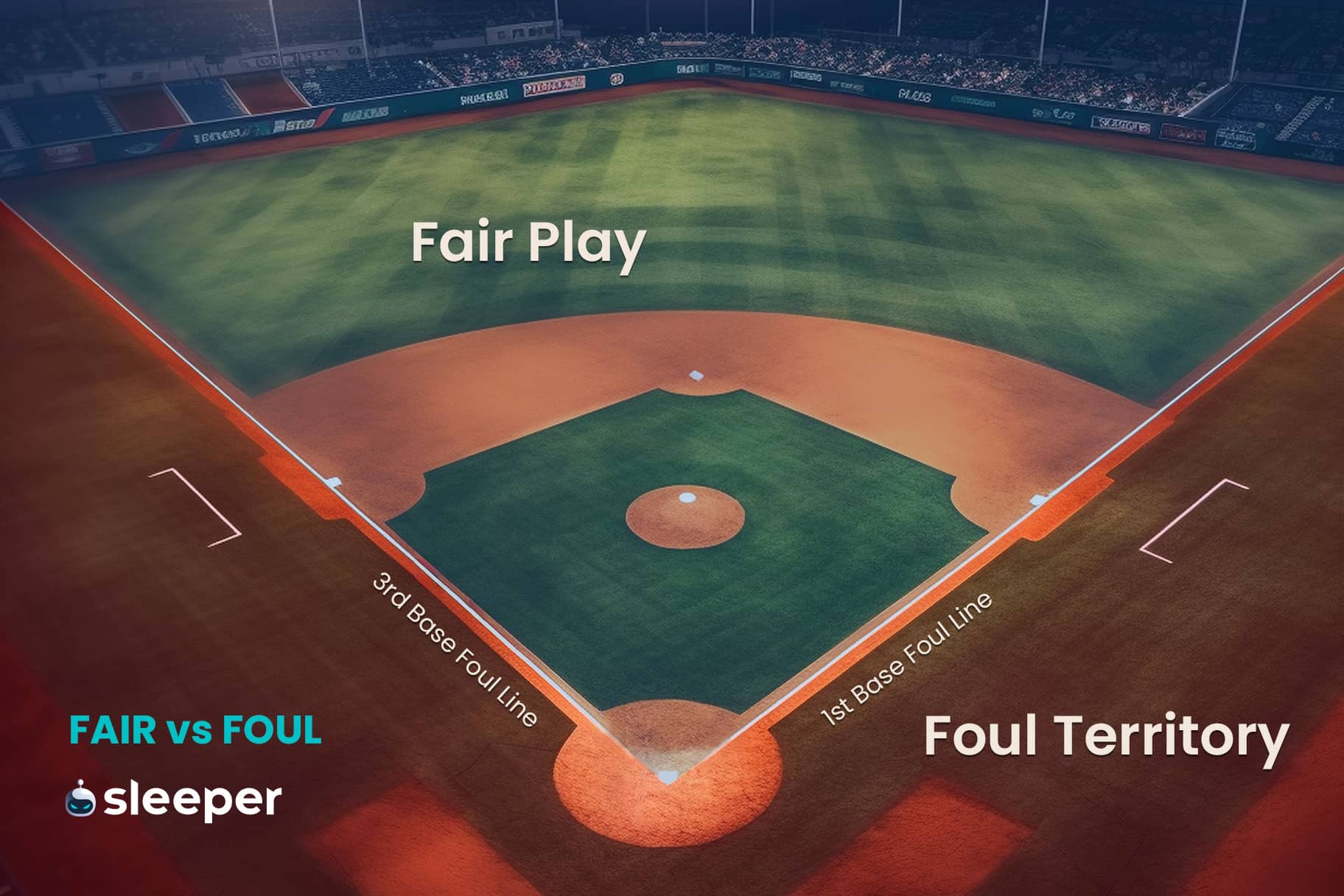

The first-base line extends in a straight line from home plate to the right-field foul pole, with the third-base line doing the same to the left-field foul pole.

However, the distance to those foul poles, the distance of the other walls in the outfield and how much foul territory there is between the baselines and the fans’ seats varies from one ballpark to the next.

4. The Bases

Beginning with home plate and working counter-clockwise through the infield, there’s first base, second base and third base before getting back to home. Baserunners must progress in that order, touching each base along the way.

In MLB, the square bases are now 18 inches along each side, while home plate (at all levels, from tee ball on up to the big leagues) is a 17-inch wide, irregular pentagon.

5. Balls and Strikes

For it’s one, two, three strikes you’re out at the old ball game.

Or is it one, two, three, four balls you walk? How come sometimes the superimposed box on TV will show that a pitch was a strike but the umpire calls it a ball, or vice versa? And how many times is the batter allowed to foul a pitch off?

It can all get a little confusing, but let’s get down to brass tacks.

If a batter swings and misses at a pitch, it’s a strike. And if the batter already had two strikes, then the batter is out.

Same goes for called strikes, which is when the batter does not swing, but the umpire declares that the pitch went through the strike zone. That zone is supposed to be the width of home plate, above the batter’s knees and below the ill-defined midpoint of the batter’s torso. But, for the time being at least, umpires are humans, not robots, and sometimes make mistakes.

If the hitter doesn’t swing (takes the pitch) and the umpire deems it was outside the strike zone, that’s a ball. If the hitter has already drawn three balls, the fourth results in a walk (or base on balls) and first base is awarded to the hitter.

A foul ball is when the batter makes contact with the ball, but does not hit it into fair territory. A foul ball counts as a strike if the batter had either zero or one strike before that pitch. However, a foul ball when the batter already had two strikes is effectively just a do-over, as the count does not change (unless it’s tipped into the catcher’s mitt; then it’s a strikeout).

Because of foul balls, there technically is no limit to how many pitches there might be in a single plate appearance, and there have been many instances in MLB where an at-bat lasted well over 10 pitches.

6. Hits and Outs (and Errors)

When the batter puts a pitch in play, one of two things will happen.

If it’s a home run or if it falls in fair territory and the batter reaches first base (or second base for a double, or third base for a triple) before the defense records an out, that’s a hit. A good MLB hitter will record a hit in around 30 percent of his at-bats.

The other option is an out.

If a fielder catches a ball in the air, that’s a flyout, popout or lineout. Regardless of how you classify it, the batter is retired, and the fielding team is one step closer to being out of that half inning.

If the ball is hit on the ground and the defense is able to get the ball to first base before the batter gets there, that’s a groundout.

There are a bunch of other ways to record outs, including force plays, tags, double plays, catching a base stealer, etc. But the above examples are the basics.

There are also errors in baseball, which is when the official scorekeeper deems that the defense should have been able to record an out, but made a mistake either fielding the ball or throwing it. Errors count as neither hits nor outs, but they do result in a player reaching base or advancing an additional base.

7. Runs

A run is simply when a batter makes it all the way around the bases, safely returning back to home without getting out.

See also: Understanding the Scoring in Baseball

8. Pitch Types

There are more than a dozen different pitch types. Fastballs come in the two-seam, four-seam, cutter and sinker variety. Breaking balls (slower than fastballs, but with way more movement) include sliders, sweepers, curveballs and, the eternal crowd-pleaser, knuckleballs. And then there are the off-speed pitches, like changeups, splitters, forkballs and screwballs.

No one throws every type of pitch, but some pitchers might have six or seven in their arsenal, constantly keeping hitters guessing what’s coming next.

9. Stealing Bases

Base stealing is the art of advancing a base without the ball being hit. It’s when a baserunner takes off as the pitch is being thrown and tries to get to the next base before the catcher throws him out.

Basic Baseball Statistics

Every sport has statistics, but no sport loves its stats quite like baseball.

Baseball has volumes of various simple stats, advanced stats, sabermetrics, pitch-tracking data, bat-tracking data and more than enough numerical nonsense to make your head spin a few dozen times.

Let’s stick with the basics, though:

Batting Stats

- Plate Appearances (PA): The number of times a hitter comes to the plate.

- At-Bats (AB): Plate appearances minus walks, hit by pitch and sacrifices.

- Hits (H): Any time a batter reaches base safely via a single (1B), double (2B), triple (3B) or home run (HR).

- Batting Average (BA or AVG): Hits divided by at-bats.

- Runs (R): When a baserunner scores.

- Home Runs (HR): Hits that result in the batter immediately reaching hom and scoring a run, either by mashing the ball over the outfield wall or an inside-the-park effort.

- Runs Batted In (RBI): When a batter’s hit (or walk, or being hit by a pitch – and in some cases even making an out) directly results in runs being scored. For instance, a grand slam (a home run with a runner on each of first, second and third base) is worth four RBI.

- Stolen Bases (SB): The number of times a baserunner steals a base.

- Base on Balls (BB): Drawing four balls and earning a walk.

- Strikeout (K): It’s three strikes and you’re out. (For scorekeepers, a swinging strikeout is a normal, forward-facing K. If the batter is called out on strikes looking, it’s a backwards ꓘ.)

Pitching Stats

- Innings Pitched (IP): The number of outs recorded by a pitcher. One out is called and calculated as a third of an inning (since it’s one of three outs needed), but is expressed as .1 IP as opposed to .333 IP. So, if a starting pitcher makes it through five innings and gets two outs in the sixth inning before being replaced by a reliever, that pitcher is credited with 5.2 IP.

- Earned Run Average (ERA): The number of earned runs allowed (runs scored minus those that scored because of errors) divided by innings pitched, multiplied by nine. So, if that same starting pitcher allowed three earned runs in 5.2 IP, they have an ERA for the day of 4.76 (nine times three divided by five and two-thirds.).

- Walks + Hits per Inning Pitched (WHIP): Exactly what it looks like. Anything below 1.25 is generally considered a good WHIP.

- Wins (W), Losses (L), Holds (HD) and Saves (SV): The winning team will have a pitcher (often the starting pitcher) credited with a win, while the losing team will have a pitcher credited with a loss. In close games, there will also often be holds and saves awarded. The former is for relief pitchers who enter the game with a lead of three runs or less (or with the tying run on deck, at bat or on the bases) and depart without blowing the lead and recording an out. The latter is for relief pitchers who enter with the lead with the same stipulations and finish the game to secure the win.

Fantasy Advice for Baseball Beginners

Now that you know a bit more about baseball and its key statistics, you might be ready to dip your toes into the vast world of fantasy baseball.

We’ve put together a full beginner’s guide to fantasy baseball if you want a deeper dive on the ins and outs of it, but the general idea is that your fantasy team gets credit for what happens on the real-life field.

For instance, if you draft Aaron Judge, have him in your starting lineup and he hits a home run for the New York Yankees, congratulations, your fantasy team also gets credit for that home run.

If a full-roster, full-season fantasy league is a bit too daunting of a first step, Sleeper Picks might be more your speed, provided you are in a location that permits you to play Daily Fantasy Sports (DFS). For that, all you do is pick two or more players and predict whether they will do better or worse than their daily projected stats (runs, hits, HR, etc.) So, sticking with the Judge example, you could pick whether he’ll hit more or less than 0.5 home runs on any given day.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why aren’t MLB park dimensions uniform?

It’s weird, right? The Boston Bruins play on the same-sized rink as any other NHL team. The Boston Celtics play on the same-sized court as any other NBA team. But the Boston Red Sox randomly have a gigantic green wall in left field.

The “why” is simple, ancient history: Teams building original stadiums more than a century ago had to do what they could with the plots of lands that they had, and MLB allowed slight differences in where outfield walls were placed and/or how tall they could be. Thus, as new stadiums were constructed, there was no standard in place and various intricacies continued to be added.

When can/must baserunners advance in baseball?

Pardon the oxymoron, but this might be the trickiest basic of baseball.

On ground balls, baserunners are forced to advance unless there is an empty base somewhere behind them. If you’re on second and there is a runner on first, you must try to get to third on a ground ball. It is a force play at third, meaning if a fielder with the ball touches the base before you get there, you are out.

However, if you’re on second and there is not a runner on first, you don’t need to go to third on a ground ball. If you do try to get to third, it is not a force out and you must be tagged with the ball before you reach the base.

On fly balls, runners generally stay put but have the option of attempting to advance by “tagging up.” For example, a runner on third base can try to score on a fly out to the outfield, but that runner must be in contact with third base either as the catch is being made or at some point after the out is recorded. If a runner scores on a fly out, that is called a sacrifice fly and the batter gets credited with an RBI (without it hurting his batting average).

What the heck is the infield fly rule?

Now we’re going beyond the basics and getting into less common scenarios. It’s a frequently asked question, though, because few understand the rule.

An infield fly is when – with fewer than two outs and at least one runner on base who would be forced to advance on a ground ball – the batter pops out in the infield (or marginally into shallow outfield). When that happens, if the umpire calls out the infield fly, the batter is immediately ruled out and the baserunners can retreat to their bag. It’s as if the catch was made at the instant the umpire makes the call, even though the ball is still in the air.

The reason for this is to prevent the fielder from intentionally dropping the ball to try to get a force out or even a double play, since the baserunners would otherwise be stuck in no-man’s land, not knowing whether they need to attempt to advance.

The Closer

So, there you have it: the basics of baseball.

Hopefully this guide helps you better appreciate watching and/or playing the sport. And if you want to get into fantasy baseball, give Sleeper a try. The app is top notch, full with MLB alerts and news, and the fantasy offerings are plentiful.